Well hello, 2021. Happy new year! (Or how about a ‘happy new day, everyday’?)

I thought I'd start writing before the year began, but had to modify plans as my laptop wasn’t with me for most of January.

As it's been so long, let me begin with a joke.

Q. What do I (the writer), you (the reader), Santa Claus, club music, bored politicians and photography have in common?

Ans. Dark rooms.

Hmm. Did that make no sense?

Fair enough, so here’s an explanation to stretch your imaginations a little—

You & I are the result of a dark room, literally. Flashback to your ‘original’ birthday; then subtract another 9 months, give or take a few. Your parents were probably praying to God for a baby to carry forward the family name, which led to you.

Unless you think they were courageous enough to have the lights on while they were…praying.

If one fine year kids decide to form a worldwide union & not go to sleep on Christmas Eve, would Santa still sneak into well-lit rooms to hide gifts?

Human beings usually play groovy beats and club music in darkened spaces.

Bored politicians have been caught on camera watching adult entertainment on their phones in Parliament. Don’t you think they wished the seating hall was much darker?

Darkrooms in photography is what this issue broadly explores. (Surprise!)

Issue #2 is a small, exciting journey touching on biology, chemistry, illusions, psychology, art & our memories. Jesus Christ features in a cameo.

So here’s to a cheerful read discussing (among other things) negatives!

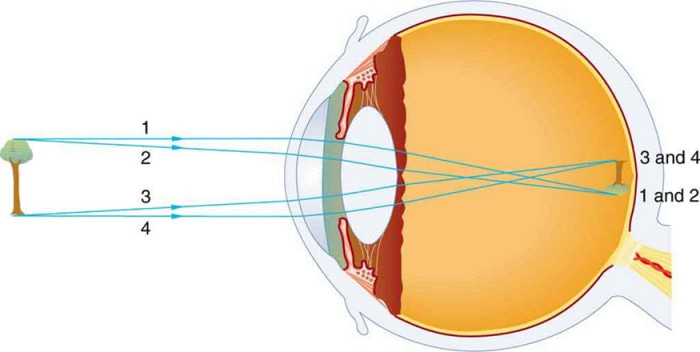

When we view any object, its image forms in reverse on our retina. The rod & cone cells lining the retina convert the light into electrical signals, which the optic nerve (at the back) ultimately transmits to the brain’s visual cortex for our neurons to re-reverse & perceive as a whole.

Welcome to darkroom 101.

Let the rays of light entering through your pupil be a torch beam, & think of the interior of your eye as a room.

Is a torch as effective in a room full of multiple sources of light as it is in a dark room? Nope.

The composition of our eyes, therefore, ensures that the impulses sent to our brain suffer minimal interference from within.

Now, notice this diagram from 1755.

Called Camera Obscura (meaning “dark chamber”), it’s an extension of the same principle as seen (pun intended) in the eye above. Light enters the room only through a tiny hole in the wall. This procedure has been used to safely watch solar eclipses & make scientific drawings for hundreds of years.

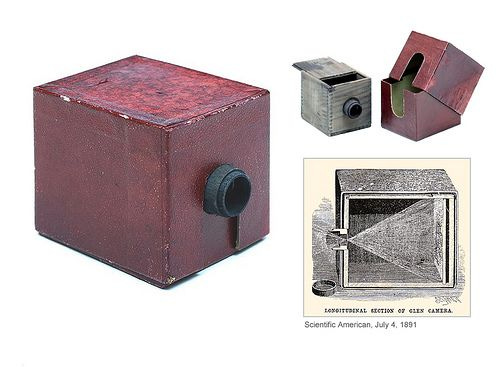

Later, a miniature version arrived: a pin-hole camera, a light-proof box also displaying reversed images on the translucent surface at the other end.

(The images could not be stored yet though; they had to be traced by hand.)

In the late 18th century, there were newer scientific developments in the field:

a lens was introduced in place of the hole to further focus the light rays, and finally,

chemical processes invented to preserve the captured images. This generally involved treating different surfaces like glass and paper with varying amounts of photochemical pigments (e.g. silver chloride), then exposing them for long periods to light so that the impressions stabilised and didn’t fade away later.

These early advances in photography involved a lot of painstaking experimentation. I’ll provide a simple visual glimpse, through a sequence of landmark photographs since the 1820s:

On a thin pewter plate coated with bitumin, we see a view outside the window:

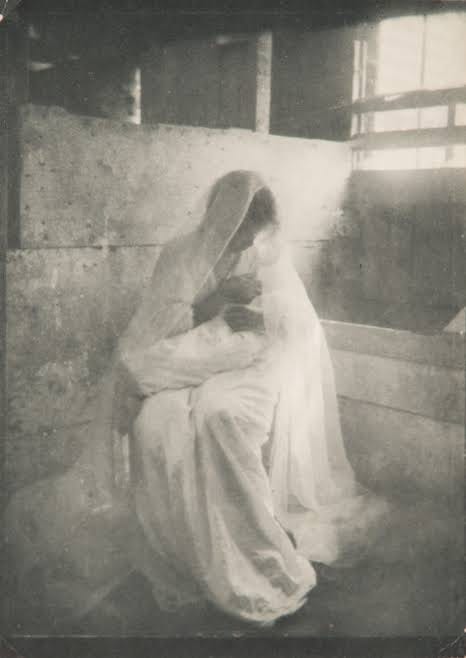

Collodion negative on glass, using the albumen silver print process:

Using newer processes on platinum:

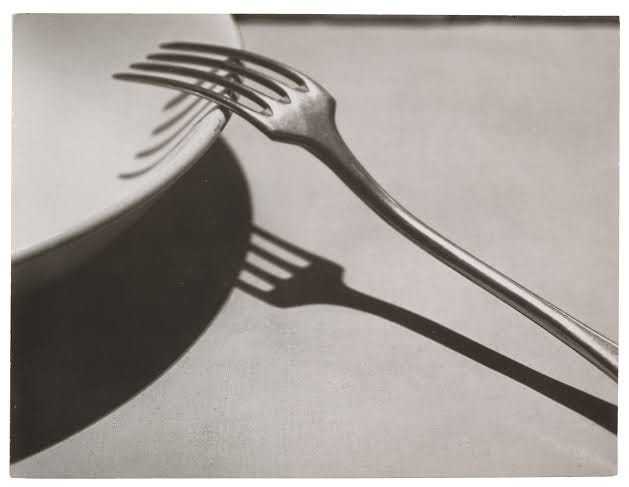

A gelatin silver print, which precedes development of modern photographic film, capturing various shades of shadow:

Taken in New York near the end of WWII, this is one of my favourite black & white photographs. A boy carries a model boat with sails across a road which features a large puddle of water in the foreground reflecting a tree’s branches. It’s hard to describe the symbolic sense of displacement the boat evokes, the waters of war having dried up.

Returning to the eyes for a bit— actually, they’re nothing as ordinary as putting cameras in our skulls and thinking that's all there is to it..

There are two things we constantly use to orient ourselves that can easily fool us: our memories and our eyes. And although only our memory appears to fail us quite often (more so as we grow older), we can also be guilty of taking what we see for granted.

If you thought your eyes functioned as a camera, the brain would be the director, its neurons picking and choosing which signals to interpret and which to neglect out of the many visual elements (like shape, size, position, motion, colour) of an object that our eyes observe; otherwise, there’d be too much information to combine into one single vision.

The best way to understand this is— what we see is itself ‘unreal’ in a way, the different attributes channeled through a unified perspective’s (our brain’s) best guess about what exactly we are seeing.

For a demonstration of this:

What do we see? A square with the lines rocking back and forth, almost rotating.

In reality, those who created it are playing with our visual perception: that’s just a stationary square consisting of little bar elements that are rotating within themselves and creating locally produced 'motion signals’ that our eyes detect. These are synchronised by our neurons, which then tricks our brain into experiencing something that isn’t there.

As Gideon Caplovitz (a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Nevada and one of its creators) elaborates:

I don’t have a rotating square detector in my brain; what I have are neurons that detect local motion, and then other neurons that integrate them. And the output of that is what we experience. So the existence of the illusion is telling us something about the way the brain works.

Neuroscientists have developed the technique of using illusions to acquire insight into how the brain functions, and it has become one of the most important non-surgical methods to conduct research. Illusions signify the errors that our brain’s perceptual ability sometimes makes, the mistakes in interpreting specific visual information (like integrating the form and motion of objects) due to the path-dependent way in which human beings have evolved.

Speaking of evolution, the Shroud of Turin is another curious artifact that lies at the cross-section of belief, illusion and photography. Radiocarbon dated to have originated in the Middle Ages around the 13th century, no one can exactly pinpoint how a man’s face was imprinted onto a piece of linen. Many have, through the centuries, claimed it to be the shroud Jesus wore while being crucified and buried.

Which would really be quite the miracle.

Do you recall this item (heavily used even during my childhood)?

These canisters would store photographic film rolls, generally ‘negatives’:

[A long time ago, we weren’t adults going all teary-eyed when re-imagining our childhood. Rather, we used to be kids itching to grow up.

Notice I use the word ‘re-imagining’. It might be the case that when we recall memories from our childhood, we aren’t actively constructing something original; however, psychologists argue that we re-create them, subjectively interpreting what we remember through the lens of who we are now, and that as we become older, we design our life’s stories using the emotions surrounding important memories to keep us going. (Hauntingly, smartly.)]

Anyway, forget the mechanics of our brain.

Before the last decade, there were hardly any mobile phones or digital cameras around. We couldn’t just instantly click anything we liked, and had to go to a shop to ‘develop’ photos with an associated cost. A camera had to be coupled with ‘photographic film’, coated with a plastic called celluloid which captured photographs on opening the shutter. Once we were ready, this film was cut into similar pieces (‘negatives’, in which the areas in the image with most light are most darkened, and vice versa), that, when exposed to light and treated chemically, projected the image onto photographic paper (a kind of paper that reacts to light). This entire process of processing & printing required rooms which blocked the entry of light to allow control of the exact amount of time the photo paper was developed under particular lighting. If you didn’t take sufficient care, you could ruin the pictures, ending up with an ‘overexposed’ photo.

But all this is history. No one uses a film camera anymore. Kodak, once the most dominant player in the commercial photography industry, couldn’t diversify its assets quickly enough in the face of a digital revolution— which led to bankruptcy in 2012 & later, restructuring. Instant digital photography became the new normal. Microchip sensors & cloud storage have essentially made our generation perfectly satisfied to collect pictures, words & movies without having to touch them physically.

Similarly, these canisters too disappeared from the very memories they served to preserve for decades.

Has having the capability to use our phones to take every image we want undervalued the magical feeling of storing memories as a solid souvenir of our lives?

On a side note, what’s both funny & tragic is how they’re being used today:

Time for some related literature. The latest novel by the brilliant David Mitchell, ‘Utopia Avenue’ (2020) is set during the 1960s. It follows the rise & inevitable breakup of an imaginary British band called Utopia Avenue. Each chapter is titled after a song written by one of the 4 members (Elf, Dean, Jasper, Griff), loosely describing the moods & events that influence the music from his/her perspective.

One such chapter, ‘Darkroom’ (you guessed it), is based around a song written by Jasper de Zoet, the band’s virtuoso rock guitarist, where he meets & falls for Mecca, a talented amateur photographer from Germany.

Listen to them developing images of the band to get a feel for the subject:

The darkroom at Mike Anglesey’s studio is crimson black, save for a small rectangle of brightness under the projector. Fumes from chemicals stiffen the air. It’s as quiet as a locked church.

Mecca murmurs, ‘One hundred seconds.’

Jasper sets the timer and flips the switch.

Using a pair of tongs, Mecca dunks the print in the tray of developer fluid and tilts it to and fro to keep the liquid moving over the paper. ‘If I do this a million times, even, still it is magic.’

As they watch, a ghost of Elf emerges on the paper, in a state of rapt concentration. Mecca has the same expression now. Jasper remarks, ‘It’s like a lake giving up its dead.’

‘The past, giving up a moment.’ The timer buzzes. She lifts the print, lets it drip, and transfers it to the stop-bath. ‘Thirty seconds.’

Jasper sets the timer. Mecca has him tilt the tray of fixing fluid while she records timings and filter types. When the timer buzzes she flicks on the overhead bulb. Jasper’s eyes hum in the yellow light. Mecca rinses the fluid from the print.

Unfortunately, she’s flying off to the United States for a career taking pictures (a memorable line: ‘I photograph what I wish to photograph,’ says Mecca, ‘for myself. I photograph what I am paid to photograph, for money.’), but not before they share the kind of romance that is the shortest (4 days & 5 nights, out of which they only meet during 3), yet will remain the longest. There is magic in the way David writes the parting scene.

This is the end. They hug. Ask if you can visit her in Chicago. Ask her to come back to London on her way home. ‘I don’t want you to go,’ says Jasper.

‘Same here,’ says Mecca. ‘That’s why I should.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘I know.’ She lifts his knuckle to her lips, then the queue shuffles her away. She looks back one last time, the way you’re warned against by myths and fairy tales. She waves from the gateway and she’s going, going… gone. A person is a thing that leaves.

It is the darkness which allows us to appreciate what the light reveals.

We’d go blind if every direction we look is entirely glowing with illumination. Instead, the outlines of shapes in our sight can be distinguished because of the relative contrast in lighting between the different things we view, which has been conditioning our brains since birth.

The ways in which we perceive the world, our habits & daily choices, actively create neural pathways inside our brain. Within these pathways, neurons ‘fire’ to establish our reactions to various stimuli. For example, we’ve all perhaps mistakenly touched a hot surface once in our life; this has led to us being wary of repeating this error. Even thinking of a similar situation alerts our cognitive perception to the inherent danger.

For most of human history, the tools we had to record & pass on such important information outside our bodies were words & sketches. Nothing else was cheap enough or consumed widely enough.

These developments in capturing images, alongside advances in sound recording, ultimately combining the two together as cinema, has gifted humanity a medium to create a living reservoir of itself. To be honest, we’ve added a brand new dimension to our pre-existing capacity for storing memories, not just an extra 1 TB of space. Sometimes, we can even remember our lives like they were films.

And we perform all this today from the comfort of our beds, lying in very dark rooms.

Not going to read this because you forgot my birthday.

JK!

Don't worry that's definitely not the disputed territory of India, I was just kidding.

But why would you write your blog in a hurry? Would you not want it to be perfect by your own standards? For us, whatever you blurt is gold, but is it the same for you?

The b&w boat photograph has just a mind-blowingly calming effect man!

Herb storehouse! XD. There is great pleasure in waiting for something or spending the effort to make it perfect. Phones have indeed ruined that by replacing it with what we call 'instant gratification'. Even if we realize it I don't think it is easy to simply walk the other way.

Loved the little bracketed portion on re-imagining.

Informative and personal. I liked it.

"It is the darkness which allows us to appreciate what the light reveals"

Bhai, it's pure gold. Really, enhanced my dimension of thinking.

Way to go!