Issue 6: More or Less?

Life isn't easily quantifiable unless abstracted upon. Nevertheless, numbers are everything.

Dancing with the Stars

As a child, I was never good at drawing/painting until the age when my parents got me enrolled at a local art school, even after which I remained barely satisfactory. I’m not sure if I remember correctly, but the reason why I joined had something to do with failing an exam (at a time when my grades were seldom bad). The test, probably a surprise, consisted of this: take a sheet of paper out of the middle of your exercise books, and draw a night sky. My classmates all scored 8+ on it, but my sheet, sadly, was returned to me with a 6 on 10. It was a testament to my teacher’s generous spirit that she still graded me fairly higher than what my submission deserved— for unlike the rest of the class, I’d handed in an unfinished work with half the sky uncoloured with my blue crayon, and most of the page full of innumerable small, dirty-penciled stars that were crammed to the point of hurting your eyesight. Because I had taken so much time sketching the stars, refusing to stop until there were too many to count, there was none left for the actual colouring.

My parents had wondered about this. They’d asked me why I spent all my time on doing something that would be perfectly adequate being represented by a few stars, a moon and a cloud or two set on a navy blue background (at that time, black wasn’t a colour we were encouraged to use as it could blot out other shapes). Who knew what my exact answer was, but the feelings I had at the time stayed with me; I was, in categorical terms, a “realist” in my head, thinking it’d be impossible to accurately depict the scene without many, ‘MANY’ stars, just like a real night sky, where the number of stars would be impossible to certainly proclaim. I was terribly aghast at my poor score, angry at myself for letting the moments slip away so quickly that there I was, a self-declared beacon of early maturity, suddenly nothing but a little boy sitting in a chair with no time left to bring the entire sky alive.

I danced with the stars, and they told me I was a polygamist.

Doing a Royal Number

It was the beginning of a lesson that I have learnt all through my life, perhaps still not completely mastered— deciding when more is less, and when less more. Today, I was reading about the 1st and 2nd Magadha empires (Bimbisara, Ajatshatru, Udayin, followed by the Shishunaga and Nanda dynasties, and the Mauryan empire, under Chandragupta Maurya, Bindusara, Ashoka, etc. respectively), really the first time vast stretches of the Indian subcontinent were under some form of central administration similar to present-day government (taxation, cities, class differences). Historians have had to make do with material remains (e.g. metal, coins, inscriptions, ruins, pottery) and literary sources (like the Arthashastra and the Indica) to put in place a coherent narrative of what seems plausible, based on the progression of human civilisation up till that point. [Some characteristic texts are too full of exaggeration to take seriously.]

In this example, the former obviously applies: the reason Ashoka is so venerated as a king, his story so mythologised, is the logical result of there being as many as 39 inscriptions bearing his royal edicts across India, not to mention the impact his transition to Buddhism and subsequent sending of emissaries to spread the religion to various foreign lands had. Depictions of his army list 600,000 infantry, 130,000 cavalry, 9,000 elephants attended by 36,000 men, together with many thousands of chariots and charioteers, all controlled by 6 different boards of government. He makes his presence felt through the ages on the basis of a sheer, permanently-lasting, voluminous legacy. The further your reach extends, the better you appear in posterity; most other rulers are scarcely this ubiquitous.

This importance of the power of numbers is reflected in other ways (beyond the obvious, such as a larger army and tax-base). Take two especially important examples, numerology and chronology, or what I call the Ramdev-Amit Shah IQ test. As we settled into being agriculturists and owning territories (it’s nice to ponder how it took the technological revolution of the 20th century to make nomadic life possible again, due to the rootless nature of digital connectivity), a natural preoccupation with ‘structure’ arose in the lives of the post-Vedic people. To defend towns from falling into anarchy in an era where communication between regions was scant, and authority provided to subordinates risked making them more powerful, wasn’t easy. Fortunately, the brahmins were at hand to save the day by creating a self-empowering corpus of fantastical literature (specifically as early-on as through the Yajur and Atharva Vedas) that embedded meanings in numbers where none existed. Post the division of the populace into ‘varnas’, which though beginning with segregation based on profession ended in perpetuating classification by birth, the priestly class demonstrated their supreme erudition by making themselves increasingly indispensable to matters of the spirit, prescribing rituals and sacrifices with extensive formulae and multi-syllabic incantations that had to be strictly adhered to for attaining any goal. Nothing less than 6 goats would do, even better if each goat bought a Coronil kit.

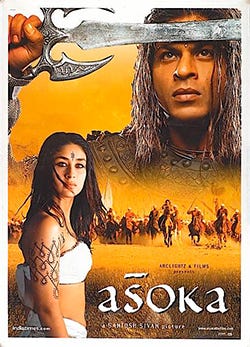

Of course, chronology is the reason we can speak with some confidence about events. Before Indians started to look into their own ancient history, however, European scholars noted a lack of a ‘sense of history’ (i.e., marking time reliably) in our ancestors. Although this was later refuted, it gives us a sense of how power functions— through (1) resources (material & informational) and across (2) time. Before the NRC came the CAA (2019 A.D.), a long time before which came the birth of Christ, the event we universally utilise to timeline history, a little before which Ashoka performed the right steps to be forever immortalised (don’t picture Shah Rukh Khan circa 250 B.C.).

Notice the relative gaps in time that the flat sentence above possesses, the first currently indeterminate, the second long, the third shorter in comparison. The Western domination of global thought is a sweet flowering of their ability to control us for as much time as they’ve seen fit. What else makes their homogenisation of our planet’s culture as potent as framing every conscious act we undertake with respect to their preacher’s birth? By population, Christians make up 31% of the world, while Islam (25%), Hinduism (15%), Buddhism (5%) and the Chinese traditional religion (5%) together constitute more than 50%. Unlike scientific standards, which have been tied to notoriously accurate measurements (the SI unit of time is defined as equal to the time duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the fundamental unperturbed ground-state of the caesium-133 atom), historical time continues to derive its sanctity from reliable old Jesus.

Real Life Endings

Here’s how numbers have been playing games with me:

A. I woke up early morning yesterday to learn how to park our car. It’s a difficult process. There’s a subtlety of motor function and innate instinct that’s irritatingly laborious to finetune, and either I was ending up sticking the vehicle too close to the wall, or too wrongly aligned. Out of frustration, eager to test myself, I decided to drive on to the road and circle back to the parking spot. Around 6 people were standing beside a public tap collecting water in their vessels on the last turn I had to make to return. The road being very narrow, my mind was buzzing with calculations. I slid the car into 1st gear and quickly rounded the corner in an effort to not overthink. Was I going too quickly, were my hands too firm on the steering? As I successfully turned the corner, I breathed a sigh of relief… until the right tyre on the back hit the pavement with a resounding THWACKKK——. Should’ve steered way more.

It took another 40 minutes before I managed to park with precision. My driving license is overpopulation’s gift to a more-or-less lethal driver.

B. Our noisiest neighbours bade final farewell to their apartment last night. They are a young couple with 2 dogs (Poco & Tina), and typically stayed inside the house most weekdays, conducting each domestic affair with the loudest voices in the neighbourhood. They owned this house as inherited property, but were on a long search for buyers due to their desire to move back to Durgapur, where they had an active garment business.

My feelings towards them were mostly of annoyance, exasperation and jaded laughter at their constant youthful chatter and extravagance. My mother, on the other hand, in spite of privately complaining at times about their excessive noise-making, had grown fond of them and the dogs, who, to be fair, were treated by them the same as humans. Every evening around 6:30 p.m., they’d ring a puja bell, quickly to be accompanied by the shrill cries of the dogs expressing their dislike of the pealing sound. As the packers & movers taped all the boxes and loaded the vans, I asked my mom if she’d miss them. She admitted she would, and on my insistence went out to say goodbye (even if we’d never even met, technically). They’d already left.

It’s funny, as they leave quite a large hole in the soundscape of this area. Listening to them earlier, I’d want them gone, but now that they have, my ears have been designing their own imitations. My mother (and most neighbours) spent a good deal of time enmeshed in the tales of their lives as being discussed daily between the two in hoarse shouts. Although they were just 2 (+2), they occupied the space of 10. Who knew nuisances could be valuable?